I’m a thriller writer. Well, I do other things, too, like suspense and even (gasp) romance. But sometimes I dwell in the dark dungeons of things that go bump in the night – the horror genre.

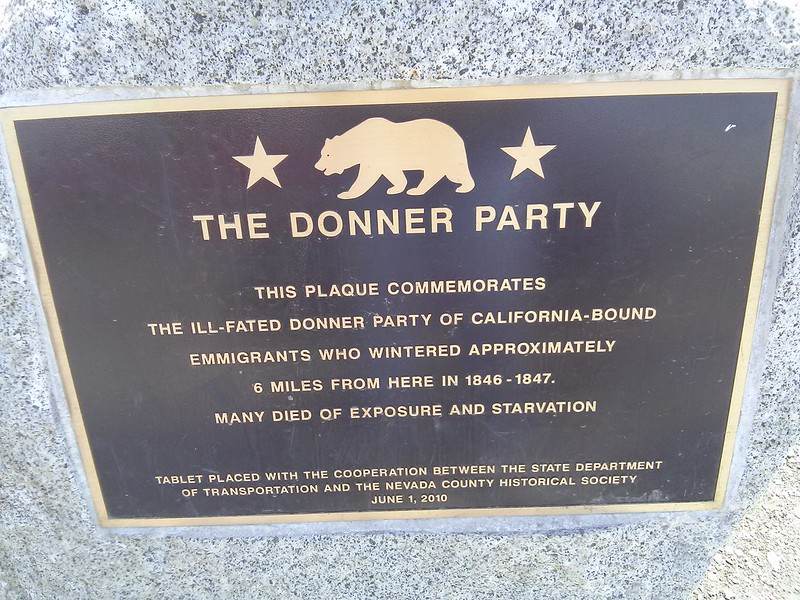

My latest short story, Communion, is set in 1846 and features a family (John Nye, his pregnant wife Anna, and her father, Ben) snowed in with an emigrant party in the Sierra Nevada mountains. The party they’re with? The infamous Donner Party.

While Communion is fiction, the Donner Party, (and what they suffered in those mountains that harsh winter of 1846), was very real. Their experiences were the very stuff of horror.

The Ill-Fated Emigration

The party was made up of folks just like us – men, women and children (God, so many kids!) who only wanted to start a new life in the promised land of California. They’d been told by people who should have known better to take an untried route called Hastings’ Cut-off. It should have trimmed 300 miles from their journey, allowing them to get to their destination (Fort Sutter in California) ahead of schedule. Instead, bad luck and trouble dogged them from their first mile along Hastings’ route.

Inexperience coupled with bad advice was a potent combination. They soon found their wagons were too heavy for the terrain, and that the terrain was steeper than they’d been led to believe. They were constantly having to adjust their route, and were forced to cut trees, move rock and grade road as they went. Hastings (who had led another party along his route a few weeks earlier) left notes along the way for the Donner party, actually revising earlier directions he’d given them. He also told them they would need to cross the Great Salt Lake Desert, an alkaline wasteland. According to Hastings, it was 40 miles wide and they could get across in 3 to 4 days. Actually, it was 80 miles of hell.

The party ran out of water half way across. Their wagons mired up in the mucky ground, and they were forced to leave some wagons and possessions behind. Some of the families had to walk when their oxen ran off and couldn’t be recovered.

They finally made it across the Great Salt Lake Desert, only to run into further troubles. The Piute and Pawnee Indians haunted their trail, stealing oxen, mules and horses, or shooting arrows into them for fun. At the Humboldt River, they found themselves low on provisions and a month behind schedule. James Stanton made a hard run on horseback across Fremont Pass to Fort Sutter and brought back some supplies, and the party slogged on, knowing they had to make it over the mountains before snowfall.

And they thought they would. They’d been told that the snow never closed the passes until mid-November, and they were at the tail end of October when they closed on the pass. But bad luck still dogged them. George Donner’s wagon axle broke, and he and his family was forced to stay behind at Alder Creek while the other members of the party kept on. These folks then made a fatal error. Thinking they had plenty of time, they chose to stop and rest their animals and themselves for several days, just below the pass. When an early blizzard blew in, they made a mad dash to get over the mountain, to no avail. The snow was too deep to cross.

That winter turned out to be the worse in memory up to that time. The snows came early, and closed the pass by the end of October. The party was snowed in, with little food to last the winter.

Their story of starvation and survival made my hair curl. Imagine – you’re responsible for your wife and children, and through a combination of arrogance, inexperience and plain bad luck, you’ve gotten them into a situation they may not get out of alive. How would you feel?

They suffered. Food slowly ran out. Metabolisms ran down. Men who’d used vast quantities of energy struggling and building road on the trip over began to die of malnutrition. Young children (and they were so many!) begin to waste away and perish. The many storms of that year drifted snow to over 15′ deep, covering the rough cabins and lean-tos at Truckee Lake (now Donner Lake) that the party had taken shelter in. It was a nightmare that looked as if it would end in all their deaths.

Sacrifice

And it would have but for the sacrifice of some brave people who, on jury-rigged snowshoes, managed to cross the divide and, fighting through ordeals we can’t even begin to imagine, make their way eventually to the settlements. Seventeen men and women, including a young man of 12, made up this party later called the Forlorn Hope. Lost in the mountains, many died from exposure or starvation. Others resorted to cannibalism, eating their fallen comrades to find strength to continue. Only nine made it out, and these would have died if they hadn’t encountered friendly Indians who helped them to the settlements. From there, planning began for relief parties to rescue the others.

But cruel fate wasn’t through with the Donner party yet. The Americans of California were in a war of independence with the Mexicans who claimed the territory. No men, money or supplies could be spared towards the rescue of the emigrants. After weeks of frustration, survivors of the ill-fated snowshoe party finally organized relief parties to bring the others out.

Those left at Truckee Lake and Alder Creek were in sad shape. Some were so weak they were unable to move from their pallets. Others were half mad. Many had died, and some of the survivors had cannibalized the bodies. All in all it took three relief parties to bring out the survivors, and even then they lost some of the weaker ones to vicious storms on the way out.

Nowadays, it’s difficult to imagine what the Donner party went through. We live safe in our thermostatically controlled homes, where when we get a chill we can turn up the heat. Hungry? Pop a pizza in the microwave. Food is never more than a trip to the supermarket away. Few go hungry in the U.S. today. We live in the lap of luxury, and most of us will never know what it’s like to make horrid, gut-wrenching decisions.

Or have to helplessly watch our children die.

We’ll never know what it’s like to survive a winter with no food and little clothing, with blizzards howling around us. We’ll most likely never have to sacrifice ourselves for our families, friends and neighbors. Or leave weaker children behind so stronger ones can survive.

And surely we’ll never be forced to eat our companions. Surely.

Our civilized natures are like the thin skins of apples over the rotten cores of our savagery. It would take very little to breach them.

Could we survive in the same situation the Donner party found themselves? Could we make the terrible decisions?

I never want to find out.